The state of mobile ad blocking: Taking stock of what the internet giants are doing to prevent (or enable) it

A look at how Apple, Facebook, Google and others are addressing user frustrations with mobile experiences and adoption of mobile ad blockers.

There is a tweet circulating right now, by a Twitter user named Ben Chase, that has clearly struck a chord. Though Chase has fewer than 900 followers, his tweet has garnered more than 31,000 likes, nearly 16,000 retweets and more than 450 replies at the time of writing. His point that has resonated with so many others? The typical mobile reading experience is cluttered with distractions, from sharing buttons to “read more” links to, yes, ads.

I have some thoughts about why news orgs are finding that people won’t read long articles… pic.twitter.com/G8Zh6GTA6w

— Ben (@bbchase) July 4, 2017

Users are rebelling against publishers’ efforts to keep them engaged and monetized, and their go-to weapons are ad and content blockers. That’s worrisome for publishers, and for the internet giants that have a share of that ad business and those that have publisher content linked to from their platforms.

With mobile accounting for a bigger and bigger piece of the digital advertising pie, ad blocking on mobile is becoming a much bigger industry concern. With so many players and competing interests, it can be hard to keep track of who is doing what in regard to mobile ad blocking. Here we take stock of how widespread usage is and the actions Apple, Google, Facebook and others are taking to address mobile ad blocking.

How bad is it? It depends where you look

In a 2016 report, Juniper Research predicted ad-blocking could cost publishers $27 billion in lost ad revenue by 2020 globally. The report’s author noted, “Adoption is being driven by consumer concerns over mobile data usage and privacy. [Consumers] are also incentivised to adopt the technology in order to reduce page load times.”

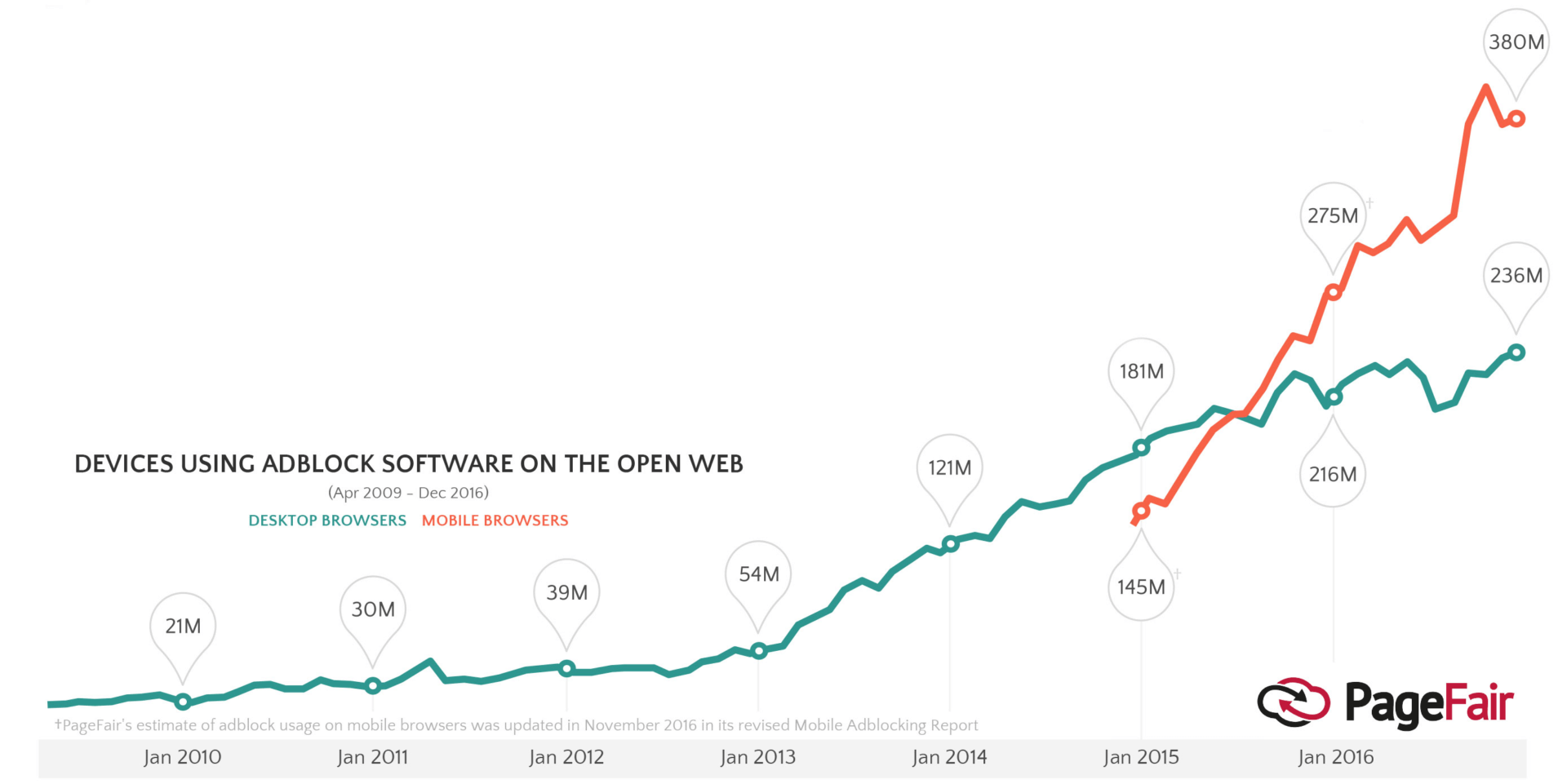

- There are some 615 million devices blocking ads globally, 380 million of them are mobile, according to PageFair’s latest report on ad blocking. Mobile ad blocking usage quickly grew by 108 million year-over-year to reach 380 million active devices globally by December 2016.

- Regionally, the use of ad blockers is highest in Asia (accounting for 94 percent of mobile ad blocking use globally), while adoption has been much slower in North America.

- In Asia, Alibaba’s UC Browser for Android devices is popular partly because of its native ad blocker. It commands around 25 percent of mobile browser market share across the region. In India alone, UC Browser accounts for roughly half of mobile browser usage.

- In the US, PageFair, which provides solutions to ad blocking for publishers, detected mobile ad blockers in use by just 1 percent of online users, with 18 percent using desktop ad blockers. That compares to worldwide usage of 7 percent for desktop ad blockers and 11 percent for mobile ad blockers.

- Usage may be higher, though, based on other estimates. eMarketer reported 9.6 percent of online users in the US have a mobile ad blocker enabled. In a survey of 1,000 US users by AdBlock Plus and Global Web Index, 15 percent of respondents said they use mobile ad blockers.

How the big players are addressing mobile ad blocking

Apple

Until Apple came along and shook things up, ad blocking had been largely a desktop concern that the industry, in the US anyway, saw as a nuisance but not much more. The introduction of content blocking extensions in iOS 9 in September 2015 opened the door to ad-blocking mobile web ads on Safari — and now Safari View Controller — and served as a wake-up call.

A month later, the IAB acknowledged its members’ role in the rise of ad blocking and introduced the LEAN Ads program, a set of more consumer-friendly ads standards as a way of addressing user complaints about slow-loading, data-sucking mobile ads.

In June 2017, Apple took a shot at the pervasive use of retargeting with the announcement that it would bolster Apple’s efforts to keep ad trackers from following users around the web via Safari. Intelligent Tracking Prevention will be baked into the next version of Safari for both mobile and desktop. After 24 hours, third-party cookies can be used for logins, but not for tracking purposes. A caveat is that the one-day window gives regularly trafficked sites and services a leg up over less popular sites and third-party ad tech. In other words, this development could benefit the likes of Google and Facebook and hurt others like Criteo and AdRoll. Apple also announced it would block autoplay video ads in Safari.

Apple, of course, thrives from the app ecosystem rather than the mobile web. Making Safari less hospitable to ad tracking has the upside potential of bigger market share for the browser with little downside for Apple. Safari is the second most popular mobile browser, with close to 18 percent share worldwide.

Apple’s other sphere of influence with publishers is Apple News. Publishers can send their content to the popular app but have so far struggled to monetize that traffic. Publishers can set up ad campaigns through Apple News, but Apple is reportedly considering opening the app to the ad-serving tools publishers are already using on their own sites, such as Google’s DoubleClick for Publishers. It will be interesting to see how this develops and whether — or more likely what — restrictions Apple puts on the types and frequency of ads allowed in Apple News articles.

In contrast to Apple, Google’s business is fueled by the web, and most web traffic is now mobile. Along with publishers, Google has the most to lose if mobile ad blocking continues taking off.

In a keynote discussion at SMX Advanced, Google’s Jerry Dischler said of intelligent tracking prevention that Google was “working through it internally, as well as with Apple” on ways to maintain AdWords and DoubleClick conversion tracking and keep remarketing working.

In October 2015, shortly after Apple announced the arrival of content blockers in iOS, Google’s Sridhar Ramaswamy said the rise of ad blocking was “a rallying cry for the industry.” It’s not all ads or all sites that consumers hate, Ramaswamy argued, but a few bad eggs ruining it for everyone else.

Here’s how that rallying cry has manifested: In September 2016, Google, Facebook, the IAB and major advertisers formed the Coalition for Better Ads, a cross-industry group that builds on much of what the LEAN ads program encompasses. In early June 2017, Google confirmed the rumors that it will begin blocking “annoying” ads that don’t meet the Coalition for Better Ads’ standards on Chrome, starting next year. That will apply to both mobile and desktop ads.

The irony that Google will itself be filtering ads — and concern that world’s biggest ad seller will be the arbiter of ad quality on the world’s most popular mobile browser with nearly half of the worldwide market share — is not lost on an industry that has complained about Google and other big ad sellers reportedly paying AdBlock Plus parent Eyeo millions to whitelist their ads through the Acceptable Ads program to get past ad blockers. But here we are.

The other front on which Google is addressing the mobile ad blocking threat is the open-source AMP project. AMP is both a response to mobile ad blocking and an effort to make the mobile web function as elegantly for users as mobile apps often do to keep them coming to the mobile web where it sells the majority of its advertising. A stated goal of the project is “to ensure effective ad monetization on the mobile web while embracing a user-centric approach.” Faster load times, less data usage and better ad security reduce friction in the user experience, lessening the likelihood of ad blocker adoption, the thinking goes.

In May, Google announced display ads would be converted automatically to AMP when served in AMP-enabled pages. The company also launched a beta in which advertisers can point their mobile search ads to AMP landing pages in an effort to make the post-click user experience better and keep users coming back to Google.

Facebook’s app-based business has largely been insulated from ad blocking. In 2016, PageFair reported that just 2.4 out of 1,000 smartphones in the US had in-app ad-blocking apps installed.

(Apple removed a short-lived threat — the Been Choice app that enabled users to block ads in apps like Facebook and Apple News, as well as the mobile web — almost as soon as it arrived in the App Store, due to privacy concerns.)

Instead, Facebook has actually focused its ad-blocking attention on desktop. Though just 12 percent of the company’s revenue came from desktop by the middle of 2016, the company said it was focusing on it because that’s where ad blocking usage is concentrated.

In August 2016, Facebook said it had implemented a way to thwart ad blockers from blocking ads on its desktop site by making ads look like regular content to the blockers. Referencing the fact that many companies pay ad blockers like AdBlock Plus to get their ads whitelisted, Facebook said of its approach, “Rather than paying ad blocking companies to unblock the ads we show — as some of these companies have invited us to do in the past — we’re putting control in people’s hands with our updated ad preferences and our other advertising controls.”

Two days later, AdBlock Plus said its user community had figured out a way around Facebook’s move. Facebook quickly plugged the hole found by AdBlock Plus users and kept Facebook ads showing on desktop.

On its Q3 2016 earnings call, Facebook CFO David Wehner attributed the company’s accelerated growth in desktop ad revenue to its ability to kneecap ad blockers.

In March 2015, Facebook launched Instant Articles for publishers to create articles that load natively inside the Facebook app. Like AMP, the main user benefit is speed. For Facebook, another key benefit is in keeping users within the app experience. Publishers keep the ad revenue from ads they sell into Instant Articles and 70 percent of what Facebook sells, but as with Apple News and to some extent with AMP, publishers have complained about monetization challenges. Facebook has since added other formats, including video ads, to Instant Articles, and in March 2017, Facebook loosened its restrictions, allowing publishers to place ads after every 250 words, rather than every 350 words, in an article.

Twitter’s own native ads don’t face significant pressure from ad blocking. Instead Twitter, like Facebook and Google, is focusing on the user experience after the link click. The June 2017 update to its iOS app included the switch to Apple’s Safari View Controller as its default browser, which has an ad-free Reader mode and supports Apple ad blockers. Links open in Safari within the Twitter app.

Users can switch to Safari’s Reader mode, which eliminates ads, along with most other page elements, or choose to have all links open in Reader mode when supported. Apple’s Safari View Controller began supporting mobile ad blockers in 2015, so users with a content-blocking app activated on their iPhones or iPads can block ads, cookies, autoplay videos and other elements from web pages on pages opened in Twitter.

Other efforts

UC Browser was mentioned earlier, but it’s worth touching on a couple of other browsers.

Samsung followed Apple’s lead and added support for content and ad-blocking plugins to the native browser on its Android phones in early 2016. Samsung Internet holds roughly 6.5 percent of the mobile browser market share in North America and globally.

Brave was created by Mozilla founder Brendan Eich, with ad-blocking features built right in. Some ads are allowed, but most display ads are blocked by default and replaced with its own ads. Publishers get a share of that ad revenue. “We are building a new browser and a connected private cloud service with anonymous ads,” said Eich when announcing Brave in January 2016. Targeting and personalization is out. Brave has not shown up on the market share trackers yet.

In the UK and Italy, mobile carrier Three is working with Rainbow (formerly Shine) to filter ads at the network level that don’t conform with industry guidelines like IAB LEAN standards.

Where we go from here

At the heart of mobile ad blocking is user frustration — over slow-loading pages, tracking and privacy concerns, and pages cluttered with intrusive ads. Users, and increasingly publishers and third-party ad tech, are beholden to whatever approaches the internet giants take in addressing these concerns. The approaches aren’t always compatible, and walled gardens make navigating this landscape that much more complex. Apple’s privacy-first stance versus Google’s tenet that harnessing user data for ad targeting provides a better experience for those users is just one example of an area of friction.

What is clear from the actions the big players are taking is that there is a sense of urgency in addressing (or embracing) mobile ad blocking. At stake is market share and billions in ad revenue. That is resulting in both strange bedfellows and sharp elbows.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for MarTech and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the martech community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. MarTech is owned by Semrush. Contributor was not asked to make any direct or indirect mentions of Semrush. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on MarTech