AP: Google collects location data when ‘Location History’ is turned off

Google says it tells users exactly what it's doing. It does, though some of the information is buried.

Yesterday, the AP reported that Google collects user location data regardless of user Location History settings:

Google wants to know where you go so badly that it records your movements even when you explicitly tell it not to. An Associated Press investigation found that many Google services on Android devices and iPhones store your location data even if you’ve used a privacy setting that says it will prevent Google from doing so. Computer-science researchers at Princeton confirmed these findings at the AP’s request.

The assertion is that Google is violating expectations of those who believe they’ve opted out of location data collection. In response to a request for comment, Google provided the following statement:

Location History is a Google product that is entirely opt in, and users have the controls to edit, delete, or turn it off at any time. As the story notes, we make sure Location History users know that when they disable the product, we continue to use location to improve the Google experience when they do things like perform a Google search or use Google for driving directions.

As the statement immediately above asserts, Google does disclose that location data will still be collected, but it’s not on the same screen as the Location History controls (in Android). Google controls on the iPhone are less straightforward.

Here are some questions raised by the AP story:

- Is Google being sufficiently clear with users about location data collection?

- Is Google’s behavior “deceptive” within the meaning of FTC regulatory guidelines?

- What’s at stake for users, beyond principle, in capturing location when Location History is off?

Google critics might answer all of these questions quickly and almost reflexively. However, I think there’s more nuance to the discussion.

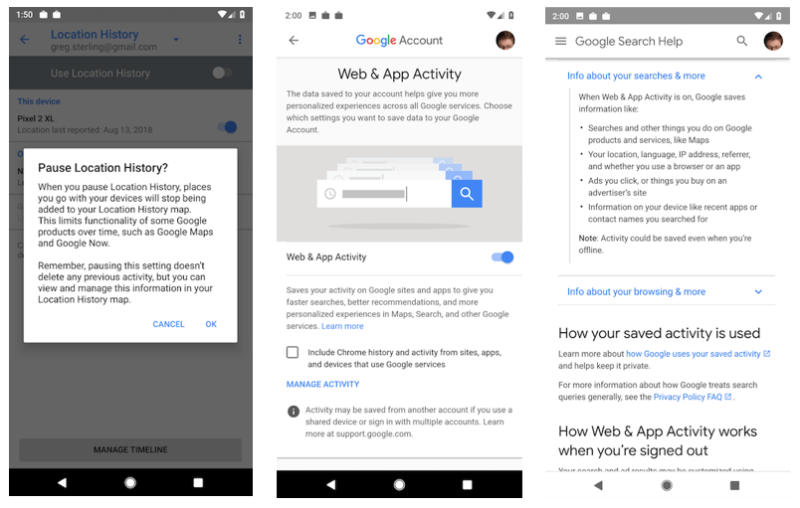

The screen shot above (from an Android Pixel, running Android 9/Pie) shows, on the left, the message users see when they pause Location History. It doesn’t indicate there that location will still be collected by other apps in some cases. It should include a link to other screens that explain further, such as those on the right.

The middle screen shows the settings for “Web & App Activity.” A click (or two) down is “info about your searches and more.” Among other things, it says:

When Web & App Activity is on, Google saves information like:

- Searches and other things you do on Google products and services, like Maps

- Your location, language, IP address, referrer and whether you use a browser or an app

Therefore, as the official statement indicates, Google does disclose that that location will still be collected — unless you disable Web & App Activity — even with Location History turned off.

Would an “ordinary user” be able to figure all this out and understand what’s going on? Probably, if the screens and language are in front of him or her. But many people won’t get there.

In 2012, Google was fined by the FTC for using cookies to circumvent “do not track” privacy controls on the iPhone’s Safari browser. The fine was more than $22 million. Is this analogous?

It probably isn’t, because of the above disclosures. But smartphone users who turn off Location History likely have an expectation that Google won’t continue to capture location data. (I don’t have any survey data to support this assertion.) But this goes back to making disclosures prominent and straightforward.

What’s at stake if Google continues to capture location data? Google asserts that it needs location to enable some apps to function properly. Undoubtedly, that’s correct; however, location data is also incredibly valuable, among other reasons, because it reveals audience behavior and purchase intent. By combining location history with Census data, companies can tell an enormous amount.

If that data is used to improperly discriminate, it’s a major problem. That’s where the government and the Constitution are supposed to come in to protect privacy. And in fairness to Silicon Valley, Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft and others have fought legal battles to prevent law enforcement from improperly accessing user data without appropriate justifications.

As long as there are legal protections against abuse of location data, there’s not a lot at stake for users in a practical sense. If Google knows where I was on Saturday (airport, home, grocery store) for the purpose of aggregating data to improve services, it’s not a significant problem, though it may feel “creepy.” That changes if unscrupulous third parties access that data for unauthorized surveillance (see China) or to discriminate against classes of people.

When governments and courts are working, we don’t need to be terribly concerned about something like whether the maps app knows where I am. But when norms and institutions break down — as is now arguably happening — we do need to worry about the implications of all the data collection.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for MarTech and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the search community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. MarTech is owned by Semrush. Contributor was not asked to make any direct or indirect mentions of Semrush. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories