Commentary

FTC says Omnicom deal is OK, as long as there’s no brand safety involved

The world's largest ad agency is forbidden from using 'political or ideological' viewpoints to determine where an ad should run.

The FTC approved Omnicom’s purchase of Interpublic Group this week, after the ad agency giant promised not to engage in any nefarious brand safety activities.

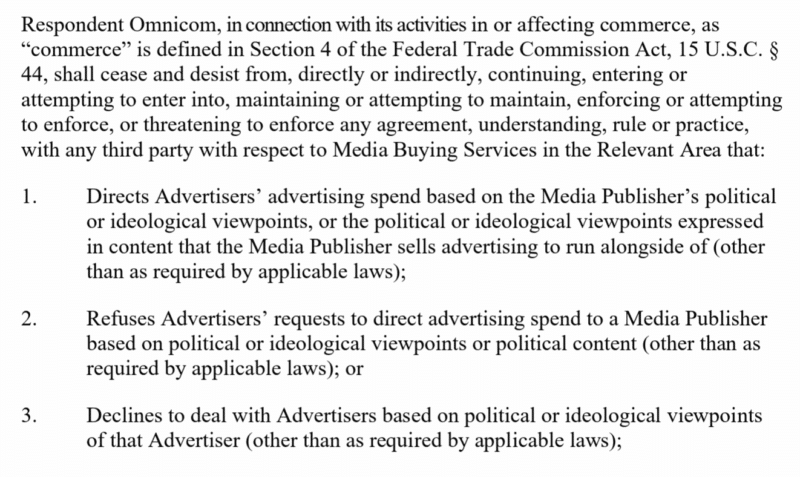

If you think I’m exaggerating, the proof is in the consent decree:

Omnicom cannot base its “advertising spend … on the Media Publisher’s political or ideological viewpoints, or the political or ideological viewpoints expressed in content that the Media Publisher sells advertising to run alongside.” It also cannot rely on third-party “exclusion lists” premised on political or ideological views to determine where it will direct advertising.

Isn’t that, in part, how brand safety works?

How we got to this point

If you were wondering, this is happening under the fig leaf of “protecting free speech” to prop up X/Twitter and help that poor waif, Elon Musk. Here’s how it came about:

Omnicom — parent company of agencies like BBDO and TBWA — is buying Interpublic Group, which owns McCann Worldgroup, in an all-stock deal that values IPG at about $13 billion. The combination will be the biggest ad company in the world, with around $25 billion in combined net revenue based on 2024 numbers.

The deal was announced in December following President Trump’s election. At the time, executives from both companies expressed confidence that the new “business-friendly” FTC wouldn’t ask any pesky questions about anti-competitiveness would quickly approve the deal. But the folks at Omnicom got caught in the administration’s Woke Ness Monster hunt. Said monster being the reason for the outbreaks of empathy, tolerance and representative democracy undermining America’s greatness.

Dig deeper: The war on DEI is hitting marketing and hurting business

In March, the FTC asked Omnicom and IPG for more info about the deal. Under normal circumstances, that’s a standard request. However, the request came just as the commission started investigating big ad firms and progressive advocacy groups for not advertising on X. Elon Musk’s media platform. (Anyone here remember the 1st Amendment? It was a great one.)

The business genius of Elon Musk

X (née Twitter) was quite popular with the public and advertisers until shortly after Musk bought it in November 2022. He paid $44 billion — twice Twitter’s market cap — for a company barely turning a profit. Musk borrowed the money to buy Twitter, even though he didn’t need to, saddling the company with the debt, and why not? He was never going to be able to earn back what he paid.

He then did everything possible to scare off advertisers. He got rid of the content moderation team and the trust and safety council, and the site began to be overrun by fake and unverified accounts. In the first month of Musk’s ownership, a bogus Eli Lilly account said the pharmaceutical company would give customers insulin, causing its stock price to drop 4.37%.

By early 2023, 50 of the site’s top 100 advertisers had stopped advertising or reduced it considerably. Later that year, amid a significant rise in hate speech, Musk posted a tweet endorsing an anti-Semitic conspiracy theory. He followed that with a tweet about the thoroughly debunked right-wing conspiracy theory “Pizzagate.”

It gets stupider

To be fair, he apologized for the anti-Semitic tweet at a New York Times event. However, he followed that with a profanity-laden rant about the companies that had stopped advertising on X, singling out Disney CEO Robert Iger. Immediately after that, Walmart stopped advertising on the site.

A report released in September found only 4% of marketers believed the platform provided adequate brand safety. Musk then took full responsibility for the fiasco and promised to make changes. HAH! He sued marketers and watchdog organizations like Media Matters for allegedly colluding in an illegal ad boycott.

Dig deeper: Hate speech on social media can significantly damage brands

He also made full use of his bromance with President Trump to strong-arm advertisers, threatening even more brands with lawsuits if they don’t spend more on X. It is unclear if the risk of action by government agencies was stated or implied. I haven’t seen any new survey numbers, but it’s unlikely these actions improved marketers’ opinion of X.

You can’t take politics out of brand safety

When I was a newspaper editor, the only rule regarding advertising was that stories about airplane crashes were not allowed next to airline ads. That’s the simplest form of brand safety, and it may also be the only form that doesn’t involve politics.

Left-leaning brands like Ben & Jerry’s aren’t the only ones that don’t want their ads running next to pro-Nazi content. A brand’s value proposition is political. It is a statement of what that brand stands for. Standing for one thing means ruling out other things.

Dove is for women and emphasizes body positivity and the idea that beauty isn’t restricted to fashion models. These are all political positions. Until about nine years ago, they were the kind of saccharine, vaguely empowering political positions that few people would bother objecting to. Because of its brand values, Dove didn’t run ads in lad’s mags like Maxim or FHM, which are the antithesis of those values.

Under the FTC’s consent decree with Omnicom, the ad agency would be at risk of legal penalties if it couldn’t show the decision was made for non-ideological reasons. In this case, readership demographics seem like a surefire defense, but with the current trend of precedent-free legal decisions, who the [expletive deleted] knows? And, if the government is willing to go after a mega-company like Omnicom, it’s willing to go after anybody.

Once upon a time, companies could spend their advertising dollars wherever they wanted. The only check on it was the consumers’ opinion. That is how free markets are supposed to work. Once upon a time, Republicans were in favor of that.

MarTech is owned by Semrush. We remain committed to providing high-quality coverage of marketing topics. Unless otherwise noted, this page’s content was written by either an employee or a paid contractor of Semrush Inc.

Related stories

New on MarTech