Native isn’t display. Stop treating it like it is.

Contributor Casey Wuestefeld reminds programmatic native advertisers that context is key to realizing this format's potential.

With consumers installing ad blockers and now browser companies following suit, not to mention ad fraud, domain spoofing, lack of viewability and disastrously poor brand-safety measures as a further body of evidence, let’s be honest with ourselves. Mistakes were made in the first decade of the programmatic revolution.

With consumers installing ad blockers and now browser companies following suit, not to mention ad fraud, domain spoofing, lack of viewability and disastrously poor brand-safety measures as a further body of evidence, let’s be honest with ourselves. Mistakes were made in the first decade of the programmatic revolution.

Don’t get me wrong — I’m an optimist. Learning from our previous mistakes is the key to future success, as long as they are not repeated. With over 10 years of programmatic experience under our belts for display and pre-roll video, what have we learned that we can apply to programmatic native? After all, it represented 84 percent of the total that eMarketer expected would be spent on native display last year, and the overall total is predicted to grow to $28 billion in 2018.

Despite its growth, marketers often overlook the operative word of native programmatic: Native. In the case of targeting, marketers are guilty of applying the same “reach-at-all-costs” strategy to their native programmatic buys as their traditional display campaigns. The result is that their brand message is placed without regard to the context of the page or even the site on which it is seen.

This needs to change.

Beware the blurred lines

Some of the confusion and lack of nuance is certainly understandable. The native programmatic space — in fact, the native space overall — has always struggled with definitions.

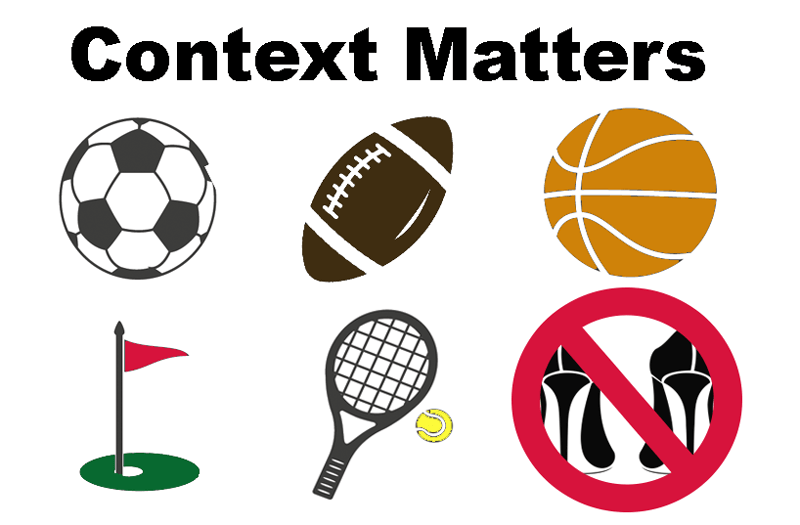

We’ve officially blurred the lines to the point that, on the programmatic front, most advertisers have given up on treating programmatic display and native programmatic as distinct entities. And here’s the problem with that: When it comes to native, context matters a whole lot more than it does in traditional display.

Consider this scenario: A brand sells designer stilettos, and thus is seeking to reach a female audience of high-end fashion lovers. Certain members of their target audience might also happen to love sports and frequent ESPN.com. As a premium publisher, ESPN.com is just fine as far as quality standards are concerned, so the publication makes the cut on the site list developed to preserve brand safety.

Under the traditional display regime, driven by audience targeting, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with serving a high-end fashion lover a traditional display ad for stilettos on ESPN.com. When she sees the banner over in the right rail, she gets it. That’s her ad, tailored according to preferences demonstrated elsewhere. But it’s separated from the feed.

However, that’s not her reaction when, instead, she encounters a content-driven placement promoting “5 Fashion Tips for This Spring” sandwiched between the Giants’ box score and last night’s Warriors highlights. That’s a bad user experience — one that causes her to stop and wonder, “Wait, why am I seeing this here? I’m on a sports site.” Stilettos are incongruous with the user experience.That’s bad for both ESPN and the fashion brand.

The context conundrum: Safety vs. scale

At present, programmatic advertising across the board is in the middle of a much-needed cleanup effort. In its initial boom, when there was a perception of infinite supply, we all saw the growing pains hit the industry headlines: bots, ad fraud, domain spoofing, lack of viewability, disastrously brand-unsafe placements. This is what happens when growth in new platforms and technologies goes unchecked.

We as an industry stepped back. We refocused. We doubled down on our audience segmentation efforts. We generated and insisted upon approved site lists for campaigns. Mission accomplished, right?

Unfortunately not. In our efforts to protect our ad spends and brand reputations, we forgot about context as it relates to our ever-growing native programmatic investments. Lulled into a false sense of security by our audience segments and site lists, we forgot about that woman who is baffled by the fashion content that’s now been injected into her sports feed.

Getting back to the basics of ad targeting

It’s time to get back to basics. Context matters tremendously in the advertiser-consumer value exchange, and it is absolutely critical when it comes to native. With native, advertisers aren’t just buying an audience. Gone are the days of targeting a specific audience and blasting impressions wherever those users can be found.

With native, advertisers are buying an audience that has shown up to a site for a certain type of content and has opted in for that kind of content alone. This fundamental principle was well understood and applied when humans were deciding which ads should appear where. It shouldn’t be sacrificed at the altar of automation.

Ultimately, however, bringing context back into the native programmatic equation will force advertisers to re-prioritize their efforts. Yes, programmatic — and specifically native programmatic — has grown tremendously. But in this age of audience and brand-safety awareness, that doesn’t mean that all our campaign efforts will scale effortlessly. Once we start layering site lists on top of audience segmentation, and then further restricting according to context, we must recognize the inherent challenges in reach.

Advertisers must abandon the “reach-at-all-costs” mentality that dominated during the first era of programmatic. It’s time to step back and refine our approach, particularly as it relates to distinguishing traditional programmatic from native programmatic.

By no means should we abandon brand safety efforts for the sake of volume. Instead, as we keep our eyes on performance, we need to rebalance and continually test new approaches to audience segmentation, site restrictions and, above all, context.

Contributing authors are invited to create content for MarTech and are chosen for their expertise and contribution to the martech community. Our contributors work under the oversight of the editorial staff and contributions are checked for quality and relevance to our readers. MarTech is owned by Semrush. Contributor was not asked to make any direct or indirect mentions of Semrush. The opinions they express are their own.

Related stories

New on MarTech