Defining Premium Inventory In Today’s Evolving Display Ad Marketplace

Almost every discussion about online display advertising will, at some point, revolve around defining “premium inventory”. Yet, despite its prevalence as a point of discussion, there is little consensus on what “premium” actually means. It is assumed, based on the chosen language, that premium is simply more valuable, both to the advertiser and the publisher. […]

Almost every discussion about online display advertising will, at some point, revolve around defining “premium inventory”. Yet, despite its prevalence as a point of discussion, there is little consensus on what “premium” actually means. It is assumed, based on the chosen language, that premium is simply more valuable, both to the advertiser and the publisher.

However, this begs the question: What makes inventory more valuable? The answer to that depends on whether you are the advertiser or the publisher. If you are the advertiser, it also depends on your specific campaign goals.

Before I begin though, I need to make one thing very clear: my aim is to focus on defining premium inventory, as opposed to premium audiences. The distinction I make between the two is that inventory is linked to publishers and their content, whereas audiences refer to individual website visitors. Inventory and audiences are related, but are simply two different things when trying to define quality, value, and performance.

In this article I will attempt to define “premium” in a way that goes beyond pure subjectivity, like campaign goals. I believe that while premium inventory can be defined vaguely as anything that meets the goals of advertisers, there is another component — session depth — that impacts the value of inventory on several levels.

That being said, it’s important to reinforce that display ad inventory can be viewed from either the perspective of the seller (publishers) or the buyer (advertisers). We will look at display ad inventory from the perspective of publishers, and how market forces encourage them to segment their inventory for maximum revenue; and from the perspective of advertisers, how they judge the value of publisher inventory.

Let’s begin our discussion of defining premium inventory by first shining some light at an often-overlooked variable: session depth.

The Missing Link: How Session Depth Affects Inventory Value

In one of my earlier articles on the mechanics of real-time bidding, I made the claim that lower session depths (i.e. earlier impressions) were higher quality, which is to say more valuable. Some perceptive readers have asked why this is the case. It’s a tough question to answer easily, but it deserves some focus, so I intend to answer it as best I can, while attempting to tie it together with the idea of how inventory is priced.

Publishers usually price the first impressions served, or lowest session depths, the highest. From their perspective, they give the highest-dollar campaigns priority, and that achieves the same result — you pay a higher price and your ads are served earlier.

We can also assume that for certain advertisers — namely brands with relatively large budgets — reach, volume, and context are key performance requirements. The earliest session depths on the most attractive websites fulfill these needs, as I’ll explain next, and since this inventory has intrinsic value, publishers can dictate higher rates.

Let’s now cover some characteristics of low session depths, and how they maximize inventory attributes like reach, volume, viewability, and opportunity.

- Reach and Volume (Quantitative)

Most website visitors only open a few pages on a website before leaving. On average, the number of pages is very low, but it varies by website. One thing is for sure: every visitor to a particular website visits at least one page. After that, there is usually a large percentage of drop-off (or “bounce”) for each subsequent page view.

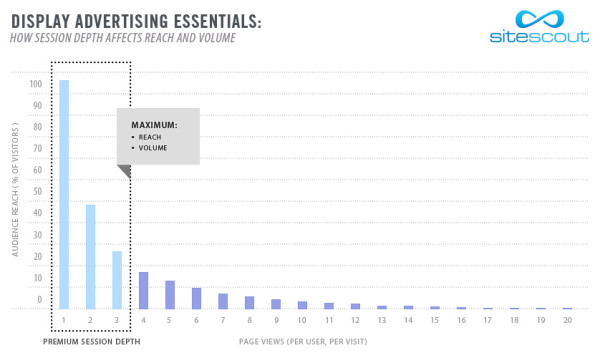

What this means is that reach (the percentage of a target audience that is reachable) is maximized at the lowest session depths. It also means that a major chunk of a website’s inventory volume (the total quantity of inventory available) is also served at the lowest session depths. As you can see in the image above, the distribution of page views per visitor is typically skewed toward the lowest session depths.

As an advertiser looking to achieve the largest audience reach, and the highest volume of inventory, targeting lower session depths provides much more certainty that you will reach your exposure goals. But there are two more benefits that come as a result of maximizing reach and volume: viewability and opportunity.

- Viewability and Opportunity (Qualitative)

Viewability is largely correlated to reach. If you have your ads shown at low session depths on a particular website, you will have the highest audience reach, and depending on the placement, the highest visibility.

There is a major benefit to advertisers when viewability is maximized: high visibility ensures that most visitors are seeing your ads. As an agency, it probably wouldn’t sit well with a large brand client if you told them that they need to refresh their browser five or six times before they see their own advertisements.

In addition to reach, volume, and viewability, earlier impressions also give advertisers an advantage, in terms of opportunity, to engage first with a given audience, whether that is selling or building brand awareness, before other advertisers get that chance.

From a brand advertiser’s perspective, the advantage of this opportunity is mostly vanity. In competitive environments, you likely want to be seen by as many people as possible before your competitors, so that you can inoculate them and build relationships first.

From a direct response perspective, the advantage of engaging earlier (or earliest) with a visitor is that you have the opportunity to make the first offer. In essence, you have a chance to make an irresistible offer and catch customers before other advertisers or merchants have a chance.

The Internet, as a medium, is interactive (i.e. “direct response”) by its very nature, which changes the value proposition of earlier impressions completely. Banner ads for direct-response campaigns are designed to elicit engagement (e.g. clicks). The first advertiser able to persuade a visitor to click a banner has effectively taken that visitor off the website. As a result, advertisers positioned to deliver their ads at later session depths lose out on a receptive lead, which was whisked away by an earlier advertiser.

If you are going after the same type of visitor as another advertiser, communicating your message first definitely gives you an advantage in terms of opportunity. This applies not only to display advertising, but also to trade shows and markets.

In a market, or a trade show floor, there is an intrinsic value to the location of your booth, similar to the session depth of impressions. There is a reason why locations nearest to an entrance are typically reserved for premium sponsors. They carry the same benefits as low session depths: reach, volume, visibility, and opportunity.

To be clear, I am not trying to imply that earlier session depths perform better for all advertisers. There is simply no evidence (that I’m aware of) to suggest that. I am also certainly not saying that higher session depths have no value, or that that they don’t perform for advertisers; that would be absurd. Performance can be found at any depth.

(Alternatively, it could very well be the case that lower session depths do perform better, but because you have to pay more, the value remains constant. In other words, low session depths could be twice as good, but cost twice as much.)

In summary: earlier impressions have certain qualities or characteristics, which make them inherently more valuable to specific advertisers with specific campaign goals. And since publishers dictate rates, they can drive higher (“premium”) pricing for them.

The Publisher’s Perspective: Revenue

It probably goes without saying, but publishers that sell ad inventory on their websites care primarily about one thing: maximizing the revenue they receive.

To illustrate how publishers typically accomplish this, let’s look at the following diagram:

As you can see, direct ad sales normally have priority in the overall ad serving “waterfall,” as controlled by publishers. The advertisers that are willing to pay the most to reserve inventory and reach the largest audience get their ads served first. In most cases, this practice will yield the most revenue for the publisher, which is why it is a common practice.

Depending on how coveted the inventory segment might be, CPM rates at this level can go anywhere from $5 to $75 CPM and beyond. Most inventory sold through direct sales are labeled “premium” by publishers, regardless of the actual performance or value to the advertiser.

On the next level below, ad sales are traditionally outsourced to ad networks at heavily discounted prices, or, often monetized with programmatic (and indirect) RTB technology. When inventory is sold through RTB platforms, each impression is auctioned off individually, based on meta-data about the visitor, like behavioral and demographic information.

In the RTB ecosystem, demand is so dynamic that it’s almost impossible to give a price range for inventory. Since each impression is valued and sold independently in an open marketplace, the traditional CPM metric becomes somewhat irrelevant and gives way to a new metric — eCPM — which is a blended figure based on averaging the winning price of thousands of impressions. In general, though, prices are usually lower when sold programmatically using RTB (but then again, so is the cost of selling it). Inventory at this level is usually labeled “remnant”. While the choice of industry-language implies lower quality, the truth is that remnant simply means that it was not sold by the publisher’s direct sales team, and is immaterial of actual quality or performance.

This practice of segmenting ad sales is probably the best way of maximizing revenue, while doing it in a fair way, and making all parties happy. At the end of the month, publishers ultimately know the objective value of their inventory, and are in the best position to speak about what segments command premium pricing.

As the diagram suggests, session depth can be used by publishers to justify higher “premium” pricing, and as a result, advertiser campaigns are configured to deliver in a priority that more or less reflects the agreed upon rates.

However, in a perfect publishing world, publishers would label their entire inventory as “premium” and charge accordingly, if they could, regardless of whether or not the inventory itself is an accurate representation of that label, and regardless of session depth or even scarcity.

In other words, what a publisher considers to be premium inventory is essentially whatever they can get away charging the most for, regardless of market demands and available supply. The dictionary definition of “premium” is consistent with this perspective: “A sum added to an ordinary price or charge.“

The Advertiser’s Perspective: Objectives

From the advertiser’s perspective, value changes on a case-by-case basis. Many people have already stated — and rightly so — that premium inventory is whatever meets an advertiser’s objectives, which naturally vary across the board.

Let’s now look at the most common campaign objectives, which usually fall into two categories: performance and/or context.

- Performance Goals

Every campaign has a performance goal of some kind, whether it’s exposure, brand lift, revenue, reach, impression volume, click volume, and so on. This means that whatever inventory segment helps achieve these goals is the most valuable to advertisers.

For branding campaigns, a concrete component of performance is often exposure, reach, and volume goals. In order to achieve these goals, advertisers often need to pay higher rates, as controlled by publishers, in order to reserve higher volumes of inventory at earlier session depths.

For direct response campaigns, performance goals and metrics usually revolve around conversions, clicks, revenue, and profit. Therefore, it’s more important that the right audience is seeing the right ads, rather than the reach or volume of the campaign alone. Achieving these goals transcends mere session depth, since targeting and messaging are more crucial in driving overall conversions.

- Context (or Relevance)

The content on a publisher’s website provides the context in which advertisers actually advertise. It is the publisher, and their reputation, audience, associations, supply of inventory, choice of placements, and so much more, that contribute to its attractiveness.

While context may not be important to every advertiser, for many it is a vital component. Having ads show up in an appropriate context is extremely important for protecting a brand’s reputation, reaching a relevant audience, and ultimately ensuring that the most value is extracted from an advertising budget.

For example, a large brand like Mercedes might be more than happy to have their products advertised on MSNBC or Forbes, but not so pleased at being placed on random file-sharing websites. In terms of relevance, all advertisers want some kind of relationship between the subject matter of the placement and the product or service being advertised. You probably wouldn’t consider advertising Rolex watches on a discussion forum for Japanese comic books – it’s completely irrelevant.

In some cases, advertisers may want to achieve specific performance goals, yet do so in brand-safe environments. While this is certainly possible, it does impose a limit on the performance potential of campaigns, since conversions can occur anywhere (like outside the bubble of brand-safe environments).

The bottom line is that session depth really only matters when it contributes to the objectives of the advertiser. And since there are certain benefits to earlier impressions, advertisers must weigh the cost of securing such inventory with the benefits, and figure out if the numbers make business sense.

Final Thoughts

“Premium” is one of those words that have become so ambiguous as to be completely useless, at least in the online advertising world. Most people can’t agree on a definition, and for good reason: it’s complex and loaded with qualifiers.

I’ve spoken with a few individuals over the last few months that have all asked for help in defining what “premium” inventory meant in some sort of clear and concise way. It’s been a tricky task to tackle, and with so many caveats and distinctions, finding a decent answer has not been easy.

Even though I agree that “premium” is a highly subjective label for describing ad inventory, there does exist a degree to which inventory can be intrinsically, or objectively, valuable: namely session depth, which is a byproduct of ad serving priority. But that is really only looking at the topic from the publisher’s perspective, which is to say: only half the story.

For advertisers, the ultimate determination of inventory value is performance. And when it comes to performance, audiences matter just as much, if not more, than simply publisher context and session depth.

Opinions expressed in this article are those of the guest author and not necessarily MarTech. Staff authors are listed here.

Related stories